February 24, 2013

Editing for an NGO: Eric Johnston’s Advice

by Stuart Ayre

What does it take to be a successful editor for a non-governmental organization (NGO)? And within an NGO, what is explicitly and implicitly expected of contributors? People have a tendency to blithely take on NGO work, editing and otherwise, without properly considering what is really being asked. Whatever altruistic intentions a person may have, what should be taken into consideration before jumping in this kind of work, for the sake of both the NGO and the individual?

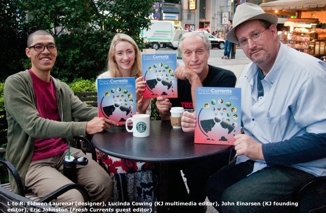

Eric Johnston, a full-time reporter for the Japan Times who has been closely involved with NGOs since the 1990s and recently edited Kyoto Journal’s Fresh Currents, addressed such questions at a candid and humorous talk hosted by SWET in early December 2012. He shared some lessons that have stayed with him from his NGO experiences, introduced, in a slightly tongue-in-cheek manner, the audience to some of the typical types of people to be found in NGOs, and also warned about some of the problems he has coped with when pursuing this line of work.

Eric Johnston, a full-time reporter for the Japan Times who has been closely involved with NGOs since the 1990s and recently edited Kyoto Journal’s Fresh Currents, addressed such questions at a candid and humorous talk hosted by SWET in early December 2012. He shared some lessons that have stayed with him from his NGO experiences, introduced, in a slightly tongue-in-cheek manner, the audience to some of the typical types of people to be found in NGOs, and also warned about some of the problems he has coped with when pursuing this line of work.

Interestingly, many of the lessons that Johnston described were not directly related to the actual skill being employed at the NGO (e.g., editing or writing), but rather addressed the importance of “soft skills.” The first lesson concerned the importance of getting under the skin of the NGO to understand its often-unwritten norms and values; the mutual understanding and agreement with these allows those working together in the organization to mesh their efforts. Getting beneath the gloss that may be presented on the NGO website takes commitment and time, but is a necessary step to properly integrate oneself into a position working with an NGO.

Johnston’s second lesson accented a major difference between working with an NGO and the average company: efficiency is often less important than the sincerity of those working there and the harmony among them. In other words, just bringing together a group of highly efficient individuals will not form the kind of dedicated team an NGO needs.

The next two lessons concern making decisions and making sure decisions do not mutate when one’s back is turned. “An editor is, ultimately, a dictator,” says Johnston. While keeping open and patient ears for gathering in everyone’s opinions, the editor also needs to shepherd such disparate views roaming here and there toward workable rules. In other words, an NGO editor needs to be a tough decision-maker who listens but takes final responsibility and pushes to ensure decisions become reality. Nevertheless, he admitted how often he experienced cases of decisions that grew legs when one’s back is turned, saying an NGO editor may sometimes be powerless to ensure that decisions stay decided.

The next two lessons concern making decisions and making sure decisions do not mutate when one’s back is turned. “An editor is, ultimately, a dictator,” says Johnston. While keeping open and patient ears for gathering in everyone’s opinions, the editor also needs to shepherd such disparate views roaming here and there toward workable rules. In other words, an NGO editor needs to be a tough decision-maker who listens but takes final responsibility and pushes to ensure decisions become reality. Nevertheless, he admitted how often he experienced cases of decisions that grew legs when one’s back is turned, saying an NGO editor may sometimes be powerless to ensure that decisions stay decided.

Many NGOs, especially those involved in environmental or human rights issues, are engaged in solving grim problems, and the grimness can apparently seep into the staff working there. This is a situation often exacerbated by long days (and weeks and months) with to-do lists that go off the page. Johnston advised us that he found it necessary to be aware to be sensitive to people who may not have time for cynical humor, even if it might be used in the expectation it would lighten the office atmosphere; one has to be aware of the focus they have on their work.

In addition, NGOs, he warned, sometimes have people he calls “troublemakers” (see below for Johnston’s thoughts on troublemakers). His approach to this problem is to nip it in the bud by identifying and isolating such people in a respectful manner. It is very important, he emphasized, not to embarrass them in front of others and to understand they are volunteers.

Hard skills (e.g., translating, writing) are naturally important to NGOs as well; an NGO cannot run on the fuel of sincerity, harmony, and diplomacy alone. Sometimes you need to advise putting the money down and hiring a professional, as time can easily be flushed away by assigning work to someone incapable of doing the job to an acceptable level.

What kinds of people are you likely to find working for an NGO? It should be stated here that Johnston expressed that NGOs are invariably filled with capable and ambitious individuals. Given the broad range of fields in which NGOs operate and the myriad of motivations people have for working for them, this is a broad question; but Johnston primed us by introducing some of the typical types he has noticed over the years.

Everyone you meet in an NGO will have a fair degree of belief in the cause and, broadly speaking, they can be split into good types (the talented) and not-so-good types (troublemakers). The talented come in two varieties, the workhorses and the natural leaders. Akin to Boxer, the horse in Animal Farm, workhorses will give everything without complaint, irrespective of what is dropped on them or how they are treated. They may not bewitch you with their conversation and they may be absent for some meetings, but they make up for their lack of social grace by actually getting the work done. The other type on this welcome side, the natural leaders, are those who people listen to and follow, be it for their charisma or their ability to materialize ideas and plans. If the philosophy of such leaders is in tune with that of the other people on the team, then projects will get off to a good start.

Johnston’s line-up of the less-desirable NGO workers consists of four types. Many of us are familiar with the first of these and will probably have a less sanitized pet-name for the first group: the all-talk-and-no-action type. Such people have lots of ideas, many of them good, but fail to understand that in an NGO, proposing an idea is often tantamount to agreeing to actually doing at least some of the work.

Next we have the attending-an-NGO-meeting-is-cheaper-than-therapy type. These are the people who, right when the details of project X are being hammered out, will hijack everyone’s ear to open up about their personal crisis and send the meeting careering off the cliff. Next in line is the moocher type, a type we hear is prevalent in the world of journalism as well. These are the people who hang around the complimentary buffet for the free cakes and alcohol, offer little or no input to the project, and are never to be seen again (unless there is another free spread).

Last in line is the self-promoter type (another type not peculiar to NGOs). Such people try to use the NGO as a mouthpiece for their own activities, and Johnston recommended cautious, diplomatic resistance when the personal projects they are pushing are irrelevant or have little relevance to the NGO.

Johnston spent the remainder of the talk discussing some practical considerations for managing work and contributing to a writing project at an NGO.

-

Deadlines in an NGO are not “dead”; they tend to move. His rule of thumb was to give a project (or any single job such as sourcing photos or proofreading) three times the amount of time you think it would take at a company. The reasons Johnston gave for the extra time invariably consumed were plentiful and were generally indicative of the hectic schedules of NGO contributors or the low priority NGO work has on contributor’s to-do lists. The other reason cited for these moving deadlines was the deliberate attempts sometimes made to delay a project with “paralysis by analysis,” a technique used by disgruntled troublemakers whose own ideas are not taken up.

-

Photos can be another source of stress in publication-related work. Often, Johnston said, because of the non-professional work that is tapped, the photos available may be poor quality (although the photographer may wonder why), may be prepared in the wrong format or resolution, or violate copyright laws. More often than not, an editor has to go back to scratch and come up with usable images.

-

Page layout, another necessary step before publishing, is another brow-furrower for an NGO editor. Partially, this can be for technical reasons: your layout artist or designer may not have a professional level of experience or knowledge of page layouts. But even the best layout artists often need time to “experiment” with different designs. Sometimes (often?), though, what the designer sees as “taking time to create the best layout'' the editor sees as “wasting time with needless experimentation.” And even if the designer is skilled, works quickly, and the layout proceeds smoothly, NGO management may also intervene with “suggestions'' at a late stage that can add to the stress of completing the publication in a satisfactory manner.

-

Learning the lexicon of the NGO is essential. Knowing your RINGOs (Research and Independent NGOs) from your BINGOs (Business and Industrial NGOs) and TUNGOs (Trade Union NGOs), for example, may well help you in a meeting; not understanding what is really meant by capacity building, common but differentiated approaches, the Doha Round, carbon sinks or the purpose of the Cartagena Protocol may well leave you out of the conversation. This is another example of advice that argues for doing NGO work at the same level of professionalism you would have for non-NGO work.

If one feels drawn to working for an NGO, it seems advisable to integrate into its working team by making sure you find its aims and activities strike a genuine chord. At such an NGO, you are more likely to have the stamina, patience, and flexibility to get the work done. Indeed, Johnston’s advice applies even when working for a non-NGO client: Actually listen to what people are saying, be clear in your decision making, cultivate diplomatic skills and collaborate with others, and do your homework. It is nothing more than common sense, but precisely for that reason, it bears repeating, especially to busy members of SWET.

(With thanks to Makoto Matsuo for transcribing the talk)